“I’ve got the gospel of land use planning in my veins,” says Ed Sullivan, who begins his 50th year of adjunct teaching at PSU this year. “I’ve lived it. I’ve advocated it. And this is an opportunity to pass it on to others.”

Originally from New York, Sullivan made his way to the West Coast in 1966, when he attended law school at Willamette University. His first job out of law school was at the Washington County Counsel’s Office, where, as a young lawyer, he had a small role in the enactment of the landmark bill SB 100, a “game changer.” That legislation allowed state and local governments to regulate the use of non-federal lands in the state—for example, to prohibit converting farm or forest lands into subdivisions. The law put Oregon on the map in the world of planning law and policy and made Oregon an outstanding example of progressive land policy.

Sullivan taught his first course at Portland Community College in 1972. A year later, Sumner Sharpe, who ran the Urban Studies department at PSU at the time (now CUPA), asked him to come to PSU. Sullivan worked as a lawyer throughout the decades until his retirement in 2014, but he continued to teach at PSU, and at Lewis & Clark and Willamette law schools. On February 2, 2022, he gave a presentation to his department at PSU reflecting on his teaching, as well as the past—and future—of Oregon’s land use, which you can read here.

Sullivan’s signature course, which he has taught for 50 years, is Land Use: Legal Aspects. Starting in 2000, he taught Oregon Land Use Law, the only class in the entire state (including law schools) that specifically covers Oregon land use. He has also taught Environmental Law and Administrative Law at PSU.

Sullivan, who is a proud PSUFA member, sat down with us to discuss the changing times, what makes teaching so fulfilling, and of course, his passion—land use law.

Take me back to 1972, when you were first asked to be an adjunct at PCC. What made you say yes?

I did it because I wanted to drill down on the academic parts of planning law, understand the subject, and make myself work at it. And secondly, to overcome my shyness. I am innately shy. You’d never know it now. [Laughs.] Sumner Sharpe was the Oregon chapter president of an organization which is now the American Planning Association. Over the years, I had provided advice and written an amicus brief for that organization. Dr. Sharpe thought it would be good for PSU to have a land use law component in the department because there was none at the time and it appeared to be an important item for planners to know.

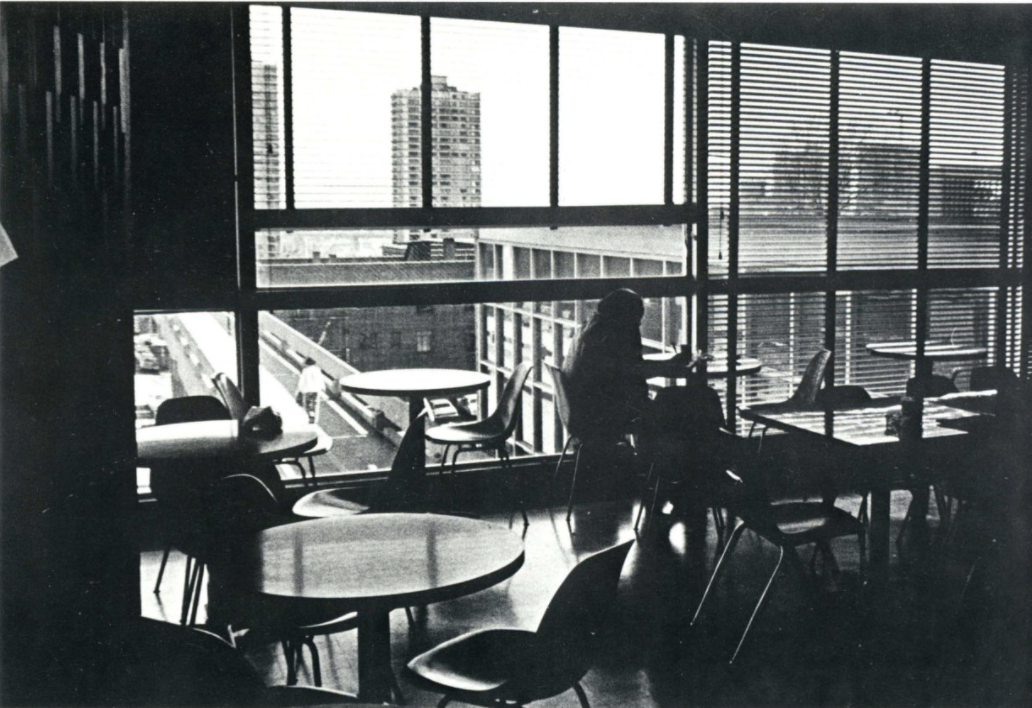

What was Portland State University like back in the ’70s?

There was a lot less than in terms of buildings, certainly a lot smaller campus. There were a lot more “regular” students—those who were just going through from high school on the way through grad school, without a stop. Today’s students are much less white, which I think is a great thing, that the university is reaching out to minority communities. In fact, minorities are now the majority at Portland State. Many more students are taking academics later in life, taking pauses during their careers, which was less the case in the 1970s. I think people are much more deliberate about their career choices today, perhaps because higher education is much more expensive. And they’re much more involved; they’re more likely to have some job or other position—maybe an advisory committee, maybe being involved in neighborhood associations—than was the case in ’73.

What’s something that a current student would have difficulty comprehending about those days?

Just how far planning law has come. In early 1973, SB 100 had not yet come down. It came down during my first year of teaching. It said—now, unremarkably—that the comprehensive plan that the local government adopts is the constitution for growth, and that all actions and land use ordinances must be consistent with the plan. That’s a big deal, and it is not the law in most states. We also didn’t have an LCDC (Land Conservation and Development Commission) at that time. So the state’s role in planning and planning law has evolved significantly over that time.

How has adjunct teaching changed for you since then?

In some ways, it’s the same: I get a contract every year, I get to teach the classes, and I don’t get any hassle, generally. The money’s better—thank you, union. And I had the benefit about four years ago to get a study grant that was done through PSUFA as part of the union contract. It paid my airfare to go speak to Australians about Oregon’s land use system and housing. So those are all good things, and better.

I’m probably the only adjunct that sits in on faculty meetings. I don’t have a vote, but three times, when accreditation comes up from national reviews of PSU’s planning program, I’ve raised the issue of the involvement of adjunct professors in the department. I complained long and hard enough that the administration finally said, “All right, you want to attend? Go ahead.” So I’m doing that. My participation is limited. Mostly it’s listening to what’s going on, and that’s a good thing. I like to find out what the faculty is thinking about, and new directions in the planning program. So I have the dilemma of answered prayers. But I’m glad I do it, and it makes me feel more participatory, so that I have my own involvement, my own stake, in what happens in the department and the school.

Besides being an adjunct professor for so long, you’ve also been a longtime member of PSUFA. Why is being a union member important to you?

Notwithstanding that I was in a white-collar job for 45 years, I was a union member while working after law school, and my dad was a union member.

Right after my third year in law school, I worked in a cannery to make enough money to get through the summer. And I joined my first union there, the Teamsters. And I believed then, and now, that union membership is essential to assure that the workers’ rights are on the radar screen of administration. Those are protected, and advanced through unions. From my perspective as an instructor, I love the idea that somebody’s looking out for me. When it comes to contract negotiations, when it comes to—God ever forbid—if I had a problem with the department, the union would be there. All of that is to the good. I have difficulty with declining union membership nationally, and with the atomization of work. And I put my money, and my time, where my mouth is.

“Teaching challenges me to rethink everything that I thought was settled.”

You talked about why you started teaching, but what made you keep doing it?

The challenge to my overly-settled beliefs, the continued need for me to think on my feet, to explain myself and my positions. The “sharing” of academics and experience—you know, that’s a BS word sometimes, but I’ve got the gospel of land use planning in my veins. I’ve lived it. I’ve advocated it. And this is an opportunity to pass it on to others.

I don’t have to do it. I don’t need to do it. But I love doing it, because I love the interaction with students. Teaching challenges me to rethink everything that I thought was settled. It gives me an interaction with the world, which I find useful, pleasant, and helpful in doing the other things that I do—in writing, and teaching elsewhere.

For everything you have shared with students, it sounds like they have given you a lot in return as well. Could you talk more about that?

Questions come out of left field and make me rethink where I am and what I’m doing. I have graduate students choose their own paper topics in land use law. I have to approve them, but I’ve always told them “pick something outside your area of comfort. And I’ll help you with it, I’ll steer you to the right person or resource.” And I learned enough from the papers submitted that it was worth it.

What words of wisdom or advice would you give to a new adjunct, or someone new to teaching?

Join the union! Because what happens elsewhere affects you, and you’re all alone otherwise. Secondly, be empathetic with your students. My classes are only night courses, so we have people with other jobs during the day that are doing this out of—not out of necessity, but because they want to advance themselves. Look inside yourself: Why are you doing this? It sure as hell ain’t the money. [Laughs.] But if you’re doing this as I did—to overcome innate shyness, to challenge yourself, to reexamine all the things that you thought were settled, you see new aspects of planning law all the time. Take it on. It’s rewarding. And do it while it’s fun. Right now it’s still fun after 50 years.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.